by Lemuel J. Lim at Genesis Law Firm, PLLC

This article provides an overview of drafting “non-disclosure agreements” (sometimes called “confidentiality agreements,”) in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions. We discuss some important language typically found in these agreements, and provide some helpful tips on other ways to keep information confidential.

I. Why is Confidentiality Important?

Confidentiality is important because any unauthorized disclosure of information can have a negative impact on the normal running of a seller’s business. To state but a few consequences:

- A company’s relationship with customers and

suppliers can be put at risk if they learn the company’s ownership is unstable; - important information, such as customer lists,

trade secrets and know-how, could be compromised; - the stability of the company’s labor force could

be jeopardized; - the business could be liable for violations of

data protection laws, antitrust laws, market abuse laws, and industry

regulations.

As a consequence, sellers will typically require any potential buyers to enter into a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) before the seller discloses any information to the potential buyer.

II. Other Ways to Maintain Confidentiality

Aside from the NDA, sellers can also protect the confidentiality of business information in other ways. Here are three tips a seller may consider applying:

- Limit the number of people involved in the

sale process. Think carefully about which members of staff must be

involved and at what stage of the sale process they should be brought in; - create procedures for how information is to

be delivered and how the buyer can view/access this information. To

achieve this, sellers may wish to purchase a data room service provider. We

have written about dedicated M&A

data rooms in a separate article; - be conscious of where meetings and communications

are held. Whether you are planning a physical meeting, or holding a

video or phone conference, the location of such meetings should be away from prying

eyes, and out of earshot from non-attendees. For physical meetings, a law firm

is typically able to facilitate meetings at their offices.

III. Mutual and Non-Mutual Non-Disclosure Agreements

It is important to determine whether only one side will be disclosing information to the other, or whether both parties will be exchanging confidential information. Sellers will almost always have to disclose confidential information to buyers, but there are some transactions where the buyer should also disclose confidential information to the seller. Parties will therefore have to discuss what form of NDA to use: whether it is a mutual NDA (“two-way” flow of information), or a non-mutual NDA (“one-way” flow of information).

Some small business owners are reluctant to request a mutual (“two-way”) NDA for fear that the potential buyer will be scared off. It is true that some buyers may not wish to disclose confidential information about themselves and so will turn down any requests to sign a mutual NDA. This is especially the case for cash-rich buyers planning to buy a business using 100% of their own cash.

Ultimately, whether the NDA is mutual or non-mutual can be highly dependent on whichever party has the greater “bargaining power.” But irrespective of bargaining power, there may be situations where the seller may wish to make a hard attempt at pressing the buyer to sign a mutual NDA. For example, where the seller anticipates that the buyer will purchase the seller’s business by using the buyer’s stock in the acquiring company, sellers would typically want to ensure that their receipt of the buyer’s stock represents a fair exchange. To do that, the seller would need the buyer to furnish information about the buyer’s business to prove the fairness of this swap. Understanding the buyer’s business is all the more important where the seller’s business owner(s) will take up a position in the buyer’s company after the transaction. Other situations where a mutual NDA would be important is where the seller has concerns about the creditworthiness of the buyer and wants to understand the buyer’s ability to tap into third party funding.

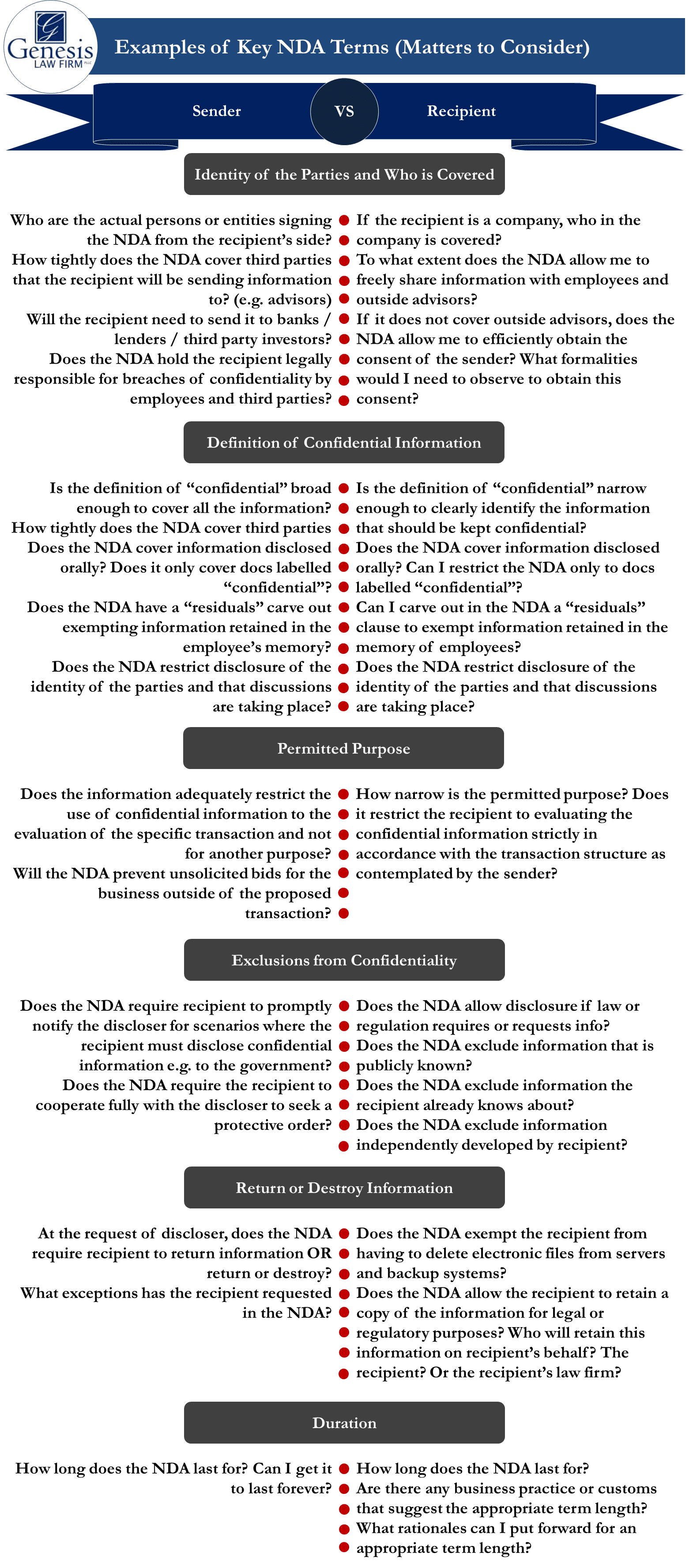

IV. Key Terms

While this is not an exhaustive list of important terms that should be included for negotiation, the following key terms should be carefully reviewed:

- The identity of the parties and who is covered

under the NDA; - the definition of confidential information;

- the purpose of the confidential information;

- the exclusions from confidentiality;

- the obligation to return or destroy confidential

information; - the length of time confidential information is

to be protected.

The Identity of the Parties and Who is Covered

Who the parties are is usually quite straightforward and will be described at the beginning of the NDA. The more difficult question is whether there needs to be any other persons or companies that should be bound by the agreement. For example, are there any subsidiaries or other companies connected to the buyer that should also be covered under the NDA? Does the recipient expect to provide confidential information to outside advisors such as lawyers, accountants, brokers, or investment bankers? If this is the case, then the NDA should make clear how these parties are to be bound.

From the buyer’s perspective, the buyer will have an incentive to make sure the NDA freely allows the buyer to share the confidential information to any employees or advisors they require. If the NDA prevents the buyer from doing so, then the buyer should ensure that the NDA has mechanisms in place to efficiently obtain the consent of the seller for these necessary employees and advisors.

From the seller’s perspective, the seller will have an incentive to make sure the NDA adequately protects the seller from the buyer’s sharing of information to third parties, especially with outside advisors and third party investors. Very often, the NDA will hold the buyer legally responsible for any violations of confidentiality by its employees or outside advisors.

The Definition of Confidential Information

It goes without saying that defining what the NDA considers ?confidential information? is of paramount importance. Sellers would want the definition to be as broad as possible to ensure that any information they provide is adequately protected. Buyers, on the other hand, would want to ensure they have certainty as to what is covered, so their motivation is to want the definition drafted as narrowly as possible.

There are four potentially “fiddly” issues that both sides will need to thrash out:

- Documents labelled “confidential.” Should the NDA only cover documentation that has been labelled “confidential” by the seller? This would clearly not be ideal for sellers as it is an administrative burden to ensure all relevant documentation are clearly marked “confidential.” It also does not provide comfort where there may have been confidential information disclosed by other means. Buyers, on the other hand, would favor this as this will provide certainty as to what information is covered under the NDA.

- Oral information. Should the NDA cover oral information conveyed to the buyer?

- “Residual” clause. Should the NDA contain a “residual” clause? A residual clause exempts from having to keep confidential any information retained in the unaided memory of the recipient’s employees.

- Non-disclosure of party’s interest in the transaction. Many buyers do not want the seller to disclose to others their interest in purchasing the business in question. They would therefore want the NDA to keep confidential the buyer’s identity and the fact that discussions are taking place with the seller. Sellers, on the other hand, may want to disclose to third parties that there are other interested parties if they are soliciting interest from other prospects.

The Purpose of the Confidential Information

The purpose (or how the information should be used by the recipient) is an essential part of the NDA. This obligation pairs side-by-side with the recipient’s obligation to keep the information confidential, and together, they form the twin pillars of the NDA.

The purpose of the NDA can be very specific. The typical language in the NDA will include a statement along the lines that: “the information provided is not to be used for any purpose other than to evaluate the transaction.”

The term “transaction” is where a recipient needs to be cautious. It can be very specific. In an important case in Delaware (Martin Marietta Materials, Inc. v. Vulcan Materials Co. (2012)) – a case which other states will give important regard to – the Delaware court held that even where information has been provided with a view to the receiving party buying the business, the term “transaction” was very narrowly defined and was limited to a friendly, negotiated merger between the two parties. It did not cover other ways to buy a business such as a “hostile takeover” (through the buying of shares in the public market). As a consequence, the court held that the buyer was in violation of the NDA.

Even though the Martin Marietta case is more relevant for NDAs where the seller is a public company, there are still lessons to be learnt for small, privately owned businesses. A chief lesson being that a party must be clear what the precise purpose of the information is under the NDA. For sellers, ambiguous language that fails to define the types of transactions that can be advanced may allow the buyer more leeway to determine alternative takeover methods – even if their approach was not what was originally envisioned by the seller. Sellers would therefore need to think carefully about how much discretion they would like to give to buyers in this respect. Again, this normally does not have much of an impact where there are no public companies involved, but the key point is to understand how narrow the NDA’s permitted purpose is.

Exclusions from Confidentiality

The obligation to keep information confidential under an NDA is almost never an absolute, unqualified obligation. There are certain situations where a permitted exception under the NDA should be made and the requirement of confidentiality excluded. Common examples of exclusion scenarios include the following:

- Where law or regulation requires disclosure.

Virtually all well-drafted NDAs will contain a carve-out clause allowing

disclosure if the information is required or requested by a government agency, regulator,

or where a court has ordered so. - The information is already publicly known.

If the information is already publicly known (and it was not released to the

public by the recipient in breach of the NDA), then it would be redundant for

this information to be protected under the NDA. - The information was already known to the

recipient. Similar to the point above, if the recipient already knew

about certain information, perhaps because the recipient received it from

another party who had no confidentiality obligation to the disclosing party, an

argument may be made that it would be inappropriate or unfair for the recipient

to be legally bound to keep this information confidential. - Where information was independently

developed without reference to the confidential information. Again,

this exception is similar to the former two. The general principle behind these

carve-outs is the rationale that if the recipient “already knows” the

information because they independently worked it out without reference to the

confidential information, why should this information be protected?

In relation to the first exclusion (where law or regulation requires disclosure), sellers may wish to negotiate language to mitigate the impact of these exclusions to confidentiality. For example, a seller may negotiate a clause stating that the recipient must give as much advanced notice as possible before disclosure occurs so that the seller can get a protective order. In addition, a seller may also request the recipient cooperate fully with the seller to seek a protective order or carry out other protective actions.

The Obligation to Return or Destroy Information

Most NDAs will contain a clause stating that the recipient should return or destroy information at the request of the discloser. This obligation usually kicks-in when one side decides to terminate negotiations and not proceed further with the transaction.

The difficulty here is that this requirement must be counterbalanced by practical considerations and record-keeping obligations the recipient may have. Consequently, the buyer may wish to negotiate with the seller to carve out an exception so that the recipient does not have to delete electronic files from servers and backup systems.

In addition, buyers may also have duties to retain a copy of the information for legal or regulatory purposes. This may not sit too well with the seller. However, a common workaround is to have the recipient’s law firm keep a copy on behalf of the recipient to satisfy their legal duties.

The Length of Time Confidential Information is to be Protected

Exactly how long the NDA should last for is one of the most heavily negotiated parts of an NDA. From the disclosing party’s perspective, the argument is that the NDA should go on forever to protect extremely sensitive information. On the recipient’s side, the argument is that an eternal NDA is unreasonable, mostly because it is impracticable. The recipient’s argument could go down the line of: “it would be really hard to police an agreement many years later, and in any case, most of the information provided would probably be stale or useless by then. Why then should I keep the obligations forever?”

There are no hard and fast rules as to what the appropriate timeframe should be. There are many factors involved. For example, businesses with a lot of sensitive intellectual property may result in longer term NDAs. Business customs and trade practices can also affect what is deemed an acceptable time limit.

V. “Super-Sensitive” Information

Where a business is highly dependent on a trade secret, “know-how,” or valuable intellectual property, it is not unusual for the discloser to have a second NDA reserved for the disclosure of “super-sensitive” information.

Here, timing and documentary control are key. For example, the seller may, under the first NDA, disclose the existence of some highly-sensitive trade secret that will be made available at a much later stage. The seller may impose the condition that the buyer will not receive such information until a firm contractual commitment to purchase the business has been signed. In addition, the seller may also make disclosure subject to the signing of a second NDA specifically covering the super-sensitive information in question.

In these scenarios, it may also be prudent to impose practical controls such as disclosure through a secure data room. As mentioned earlier, we have written about secure data rooms in a separate article.

VI. Summary

Below is a summary of key terms for each side to consider.

We hope you found this article helpful. Our firm believes in making quality information available online free of charge; and, in that vein, we’ve written on numerous related topics. We encourage you to visit our firm’s business resource page.